| Home | Books | Buy | Appearances | Op-eds | Reviews & Interviews | Bio | Contact & Media |

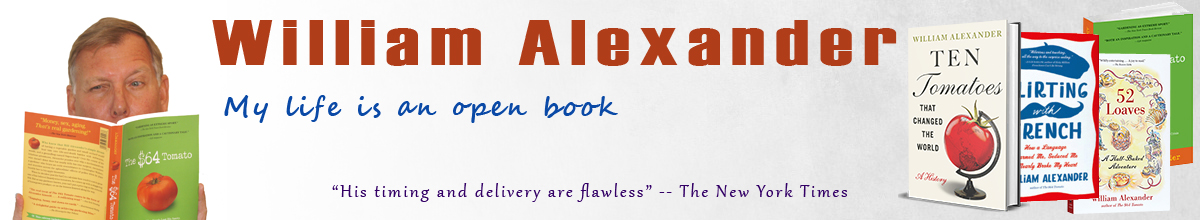

Ten Tomatoes That Changed the World

Reviews of

Flirting with French

The New York Times Book Review

Reviews of

52 Loaves

Chocolate & Zucchini

Reviews of

The $64 Tomato

| Richmond Times Dispatch |  |

The funny, often self-deprecating style he used in The $64 Tomato transfers well to 52 Loaves.Anyone who has baked bread -- or yearns to -- will recognize William Alexander's "52 Loaves" as a quest book. The quest? To re-create the perfect loaf of peasant bread he tasted at a restaurant. Once. Many years ago. Never mind that he's not trying to get home to Penelope or to find the Holy Grail. As the book's subtitle spells out, this is "One Man's Relentless Pursuit of Truth, Meaning, and a Perfect Crust." And "relentless" doesn't explain the half of it. Not only does Alexander bake a loaf of bread each week for a year, he also tries to get a bag of sourdough starter through airport security, builds an outdoor bread oven and plants red winter wheat in his vegetable garden in New York's Hudson River valley. When a neighbor asks him what he's doing in the garden, he answers: "Baking a loaf of bread. From scratch!" If you're thinking Alexander's garden is a long way from the Great Plains, you're right, but why would a little matter of geography stop as determined a bread baker as Alexander? Wait. Maybe "determined" is the wrong word. "Obsessed" may better describe Alexander, whose bread research takes him to communal ovens in Morocco, the Ritz cooking school in Paris and a medieval monastery in Normandy. Fans of Alexander's first book will recognize the approach, as well as the long subtitle, from "The $64 Tomato: How One Man Nearly Lost His Sanity, Spent a Fortune, and Endured an Existential Crisis in the Quest for the Perfect Garden." In that book, Alexander figured out that producing one Brandywine tomato in his backyard vegetable garden cost him $64. That seems like a bargain, when you consider what he must have spent chasing the perfect loaf in America, Africa and Europe. The funny, often self-deprecating style he used in "The $64 Tomato" transfers well to "52 Loaves," even though his bread quest takes a more serious turn than I remember occurring in his first book. This time, it's not a crisis of cost; it's a crisis of faith. And we're not talking about faith in his bread, but he has little of that, either. He's way too hard on himself and his bread. Even when expert bakers praise it, especially its crumb, he doubts their sincerity. In his search for perfection, he tries many techniques, including the no-knead bread made famous by The New York Times' Mark Bittman. Alexander dismisses that approach: "Making this bread had been about as much fun as doing the dishes." Then comes a light-bulb moment. "This isn't simply about lunch," he realizes. "The process needs to be rewarding." It takes him a long time to apply that thinking to his own bread. He starts enjoying himself only when he realizes that, even with bread, it's the journey, not the destination, that's important. Whether Alexander ever makes the perfect loaf turns out to be secondary to his real quest: finding himself. |

|